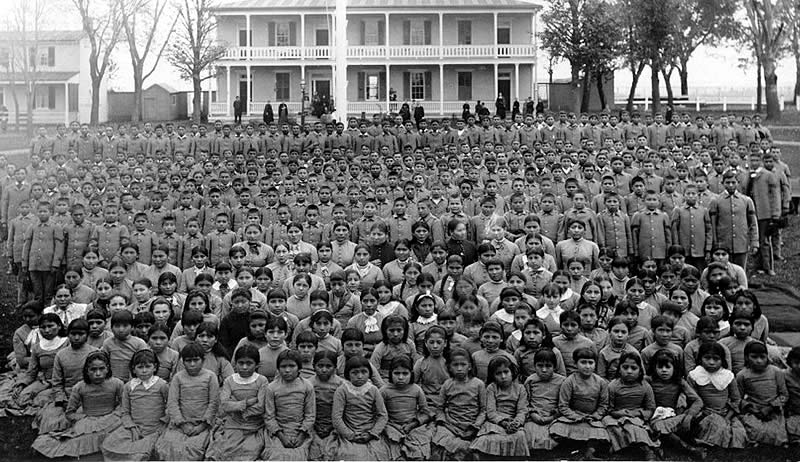

Hayward Indian School in Sawyer County, 1920. Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS- 32164.

From the 1880s to the 1930s, the policy of the United States government towards Native Americans was assimilation into white society. Native languages, spiritual beliefs, foods, traditions and family life were considered “uncivilized” so missionaries and the government opened schools on and off reservations to force children to abandon their traditions. Army officer Richard Pratt, founder of the first federal Indian boarding school, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, gave a speech in 1892 in which he summarized this philosophy as “kill the Indian…save the man.” In Wisconsin, the U.S. government ran three boarding schools, three day schools, and contracted out three additional boarding schools to religious and other organizations.

Most Native American children who went to the boarding schools were forcefully taken from their families. Subjects such as reading, writing, math, and history were all taught from the white point of view, and boys were taught to farm while girls were taught domestic work. Children were forced to cut their hair, dress in uniforms, and speak English. These schools emphasized conversion to Christianity and “citizenship training” in the foundations of U.S. society. Today we see this assault on Native cultural identity as cultural genocide. A culture cannot survive without its children to carry on its traditions.

Discipline was often severe at Indian boarding schools. Many children were malnourished and suffered physical, emotional, sexual and spiritual abuse. Schools have cemeteries on-site because so many children died. The legacy of the boarding school era and other attempts to erase Native culture still lives on as historical and intergenerational trauma.

Today, schools for Native Americans support and recognize cultural values and traditions. The Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) oversees 183 primary and secondary schools, either operated by tribes or the BIE. In Wisconsin, there is one private school, the Indian Community School of Milwaukee, and the BIE funds Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Schools, Menominee Tribal Schools, and Oneida Nation Schools. There are also currently 35 tribal colleges and universities across the country. These schools are places where Native American history, customs, and culture are honored, taught, and preserved.

After boarding schools closed, families were still separated at high rates. From 1958 to 1967, the Bureau of Indian Administration and Child Welfare League of America encouraged adoption of Native American children by non-Native families through the Indian Adoption Project. Racialized and biased child welfare policies continued to impact Native families even after formal programs ended. In 1978, 25%-35% of all Native American children were removed from their homes. This crisis gave tribal members serious concerns whether or not public child welfare and private adoption agencies had good or legal cause to remove children. Alarmed by history, statistics, and heartbreaking stories, Native American advocates pushed the federal government to pass the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978.

For more information, see Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools (NPR) and this review of “Remembering the ‘Forgotten Child’: The American Indian Child Welfare Crisis of the 1960s and 1970s.”

This material may be freely reproduced and distributed. However, when doing so, please credit Kids Matter Inc.